Chapter Five

The Habsburg Dynasty – A Global Empire

“From the birth of popery … it is estimated by careful and credible historians that more than 50 millions of the human family have been slaughtered for the crime of heresy by popish persecutors ….”

-John Dowling

After Otto the Great died in 973, his German Empire—which he patterned after Charlemagne’s and built with the moral and spiritual support of the Catholic Church—continued as Europe’s most formidable empire. After several generations, however, it decayed into a severely weakened and fragmented state.

During the 13th century, Europe entered the valley between the third and fourth resurrections of the Holy Roman Empire.

The demise of Otto’s Germanic kingdom created a power vacuum in Europe. Before long, some of Europe’s other royal houses began positioning themselves to replace the Ottonians as the power brokers of the Continent. Following the path that Charlemagne and Otto had taken before them, the first step they took in seeking to dominate Europe was to secure the support of Europe’s ultimate spiritual authority.

The seeds of the fourth resurrection of the Holy Roman Empire were sown in the 13th century, when the Habsburg family stepped up its cooperation with the Roman Catholic Church.

The Habsburgs

The Habsburg dynasty is ancient—so old that its origins are somewhat of a mystery. Early on, the Habsburgs seemed more concerned about the legacy of their own dynasty in Germany and Austria than about world dominion. But after the decline of the German Reich founded by Otto the Great, they began cooperating more with the Vatican, with the intention of resurrecting, yet again, the Holy Roman Empire.

In 1273, the Austrian king, Rudolf of Habsburg, was crowned king of the Romans by Pope Gregory X in Aachen, the seat of Charlemagne’s authority. In order to receive this recognition from the church, Rudolf had to renounce his imperial rights and his claims to territory in Italy, and to issue a promise to wage a crusade. Quid pro quo, the pope persuaded Alfonso X of Castile, a rival for the imperial throne, to recognize Rudolf. Thus, the relationship between the Habsburgs and the pope began.

Although Rudolf had been declared king of the Romans, the official title of emperor of the Holy Roman Empire was not bestowed on the Habsburg rulers for another couple of generations. In 1452, Frederick IV, king of Austria, was crowned Frederick III, the “holy Roman emperor.” That title remained in the family until the dynasty officially ended in 1806.

The greatness of the Habsburg dynasty lies more in its duration than in its dynamic leaders. Yet it did produce at least two outstanding kings who reigned successively in the 16th century: Maximilian I (1493-1519) and Charles V (1519-1556). Both these kings drastically expanded the power and influence of the Habsburgs and, of course, the Roman Catholic Church.

Maximilian I

Maximilian laid the groundwork for an international empire encompassing most of Europe and Latin America. He did this by arranging two marriages with the Spanish houses of Castile and Aragon. In one marriage, Maximilian’s son Philip married Joanna, daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella. This union united Spain and its colonial possessions in the Americas with the Holy Roman Empire of the German nation.

Like many before him, Maximilian frequently allied with and fought for the pope. When Charles VIII of France invaded Italy, Maximilian joined an alliance to drive him out. At one point he demonstrated his allegiance by turning down an offer to be made pope himself.

Encyclopedia Britannica concludes, “Great as Maximilian’s achievements were, they did not match his ambitions; he had hoped to unite all of Western Europe by reviving the empire of Charlemagne.” Though he personally failed at that task, it would continue to be pursued by his descendants.

Charles V

In 1520, Charles, the son of Philip and Joanna, was crowned as Roman Emperor Charles V. Philip died before Maximilian, so Charles ended up succeeding his grandfather. Like Charlemagne and Otto, Charles was crowned in Aachen.

Before his coronation, Charles was asked the traditional questions by the archbishop of Cologne: “Wilt thou hold and guard by all proper means the sacred faith as handed down to Catholic men? Wilt thou be the faithful shield and protector of the holy church and her servants? Wilt thou uphold and recover those rights of the realm and possessions of the empire which have been unlawfully usurped? … Wilt thou pay due SUBMISSION to the Roman pontiff and the Holy Roman Church?” (emphasis added throughout).

To these questions, Charles responded, “I will.”

After his coronation, he conducted himself in accordance with the conviction that the emperor reigned supreme. He went on to become one of the greatest emperors in history.

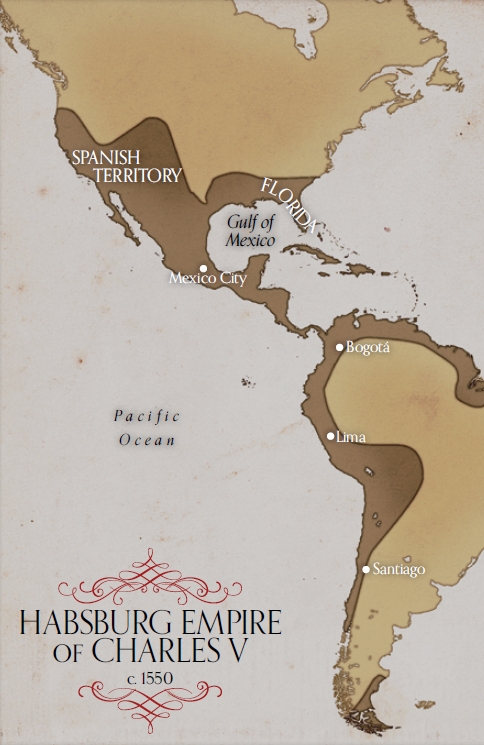

At age 19, Charles became ruler over Spanish and German dominions, including Germany, Burgundy, Italy and Spain, along with sizable overseas possessions. His kingdom became known as “the empire on which the sun never sets.”

Ten years later, in 1530, Charles was officially crowned emperor in Rome by Pope Clement VII, after Charles’s armies defeated the pope’s in 1527. In his youth, Charles was taught by Adrian of Utrecht, who went on to become Pope Adrian VI.

During Charles’s reign, vast territories in Latin America were converted to Catholicism. This began before Charles ascended to the Spanish throne. Spanish and Portuguese explorers, encouraged by the Vatican, claimed new territory for their home nations. In 1493, Pope Alexander VI gave much of the new land to Spain and, in exchange, asked Spain to convert the natives to Catholicism. Encyclopedia Britannica records that Spanish and Portuguese rulers “recognized the obligation to convert the indigenous population as part of their royal duty.” Franciscans, Dominicans, Augustinians and Jesuits traveled with the European ships. Much of the conversion of the natives took place under the reign of Charles V and his son Philip II.

The Catholic Church quickly became the most powerful institution in Latin America. Priests were held in such great respect that they could be relied on to control the masses if the army failed. The Jesuits even had their own private armies. When the Spanish government tried to reform the Catholic Church hundreds of years later, the priests turned the population against Spain. They led Latin America to independence. The fact that this vast territory became Catholic still affects geopolitics today.

During the reign of Charles V, the fourth resurrection of the Holy Roman Empire reached its apex. Not since the days of Charlemagne had a holy Roman emperor ruled over such an immense territory.

The Vatican’s Instrument

Charles V reached the height of power while the Spanish and Roman inquisitions were raging in Europe. Although the Spanish Inquisition was started by his grandparents, Ferdinand and Isabella, Charles took it to new levels. He became a deadly weapon of the Catholic Church.

At first, the Inquisition forced the conversion of Jews and Muslims. All Jews were expelled from Spain in 1492. Then the majority of Moriscos—converted Muslims living in Spain who had retained some Islamic practices—were killed.

Charles V became king of Spain in 1516 (known as Charles I). The following year, Martin Luther produced his 95 Theses, and the Protestant Reformation began. The Spanish Inquisition was aggressively expanded into Europe and brought to full fury during the Protestant Reformation. The Inquisition proved to be an effective Counter-Reformation weapon.

Many thousands across Europe were made to convert to Catholicism or were tortured and executed by the church at this time. In his 1871 book, The History of Romanism, author John Dowling wrote, “From the birth of popery … it is estimated by careful and credible historians that more than 50 millions of the human family have been slaughtered for the crime of heresy by popish persecutors ….” Halley’s Bible Handbook corroborates this figure: “Historians estimate that, in the Middle Ages and Early Reformation era, more than 50 million martyrs perished.”

That is more than twice the population of Australia—tortured and killed for not converting to Catholicism.

Charles fought forcefully against Protestantism. In 1545, he presided over the Council of Trent, which initiated the Catholic Counter-Reformation. This reformation was the Vatican’s response to the Protestant Reformation. This response was brutal, using torture and imprisonment to bring wayward Catholics back into the fold. Germany’s Protestant princes formed the Schmalkaldic League, which Charles defeated in 1547.

However, Charles was too distracted by other wars to prevent Protestantism from getting a powerful hold over Germany, though he fought hard to stop its spread. By 1547, Lutherism had grown so strong within Germany that he was forced to recognize it.

Charles V abdicated in 1556. After his reign, the Habsburg dynasty severed along Spanish and Austrian lines. The Austrian Habsburg line still assumed the title “Roman emperors of the German nation” like their predecessors five centuries before, except they no longer pilgrimaged to Rome to be crowned by the pope. The imperial office became hereditary within the Habsburg line.

By the early 17th century, the power and might of the Habsburg empire—the fourth resurrection of the Holy Roman Empire—had begun to wane. The Protestant Reformation had considerably weakened the once dominant church in Rome. On the secular side, the tide of power was beginning to shift toward France.

The fourth revival of the “Holy” Roman Empire was on its last leg, but the inevitable fifth revival of the Holy Roman Empire was on its way!